Squiggly brain: why raising a neurodivergent child is hard

All parents of differently-wired kids need a solid mental health scaffolding of their own.

“Life is difficult”, my go-to philosopher and self-development guru Scott M. Peck writes in the first sentence of his highly-revered book The Road Less Travelled. I have known this book by heart for over a decade.

Still, when I became a mother for the first time seven years ago, somehow, I expected motherhood to be mostly a bed of roses. I fantasised about my unborn son’s pouty lips spotted during the final ultrasound. I envisioned being the most present mom on Earth, cooing, singing and dotting over him.

And then he was born – all 3.1 kilograms of sheer force of nature, the least gentle and most persevering of all newborns I’ve seen. The first year of his life consisted of colicky cries and sleepless nights. And then, when he got a little older, massive, hours-on-end tantrums started. How did I react? I cried and Googled, consulted specialists and searched for relaxation techniques. And when all failed, I asked myself: “Why me?”

The currency of hope

Then, I found the book Differently Wired: Raising an Exceptional Child in a Conventional World by Debbie Reber. As a mother of a twice-gifted, neurodivergent boy with ADHD, ODD and Asperger’s Syndrome, she has explored the road less travelled since the very beginning.

“I simply know that parenting an atypical kid in a conventional world is an often lonely and difficult journey. So, I wrote Differently Wired for the parents of neurodiverse kids to know they’re not alone and to provide tools and ideas to help them better show up for their kids and themselves,” says Reber.

Her book is full of hard truths, heavy emotions and revelations about the mainstream that I could have voiced myself, yet it offers consolation and a much-welcome realisation: we’re not alone. Part a memoir, part a toolbox, Differently Wired is filled with love, compassion and – most importantly – hope. And hope is the currency neurodivergent families seem to crave the most.

Misunderstood and lonely

Neurodivergence is a relatively new psychological concept explaining brain differences that translate to various developmental, behavioural and mental health challenges – yet also often result in beautiful, quirky character traits.

According to some statistics, even 20 per cent of families worldwide raise neurodiverse kids.

Since these are not official statistics, and because they don’t consider well-functioning neurodiverse adults, real numbers may be much higher. As more children and adults become diagnosed with some form of neurodiversity, whether it’s autism, ADHD, OCD or other, as a community, we get an increased chance to learn about different – not better or worse – ways of their interaction with the world.

My son is almost seven years old, and we’ve only recently received an ADHD diagnosis for him. When he’s good, he’s really great – generous, charming, quick-witted, social, handsome, full of energy (obviously) and talented at sports. But when he’s bad, he can be horrid – disruptive, fidgety, impatient, defiant and quick-tempered. Oppositional defiance is an act that masks his anxiety, but not everyone he interacts with understands the complexity of the neurodivergent brain and its psychological intricacies.

ADHD – Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder – is a condition that presents itself in childhood but often goes undiagnosed for years, especially in women. It affects approximately 814,500 people in Australia and around five to seven per cent of the population globally. It is usually characterised by inattention, impulsivity and, in some cases, excessive levels of hyperactivity that interfere with everyday functioning.

People with ADHD may have difficulty planning, prioritising, avoiding impulses, remembering things and focusing on tasks. Which is, in essence, what an adult life of work and chores is all about.

According to a grim analysis by Deloitte Access Economics, ADHD costs Australia more than $20 billion a year in productivity losses, disability, crime, accidental deaths and suicide.

Professor Mark Bellgrove, president of the Australian ADHD Professionals Association (AADPA), admits that even though ADHD is known to most medical professionals, it is also misunderstood on multiple levels.

Squiggly brains think differently

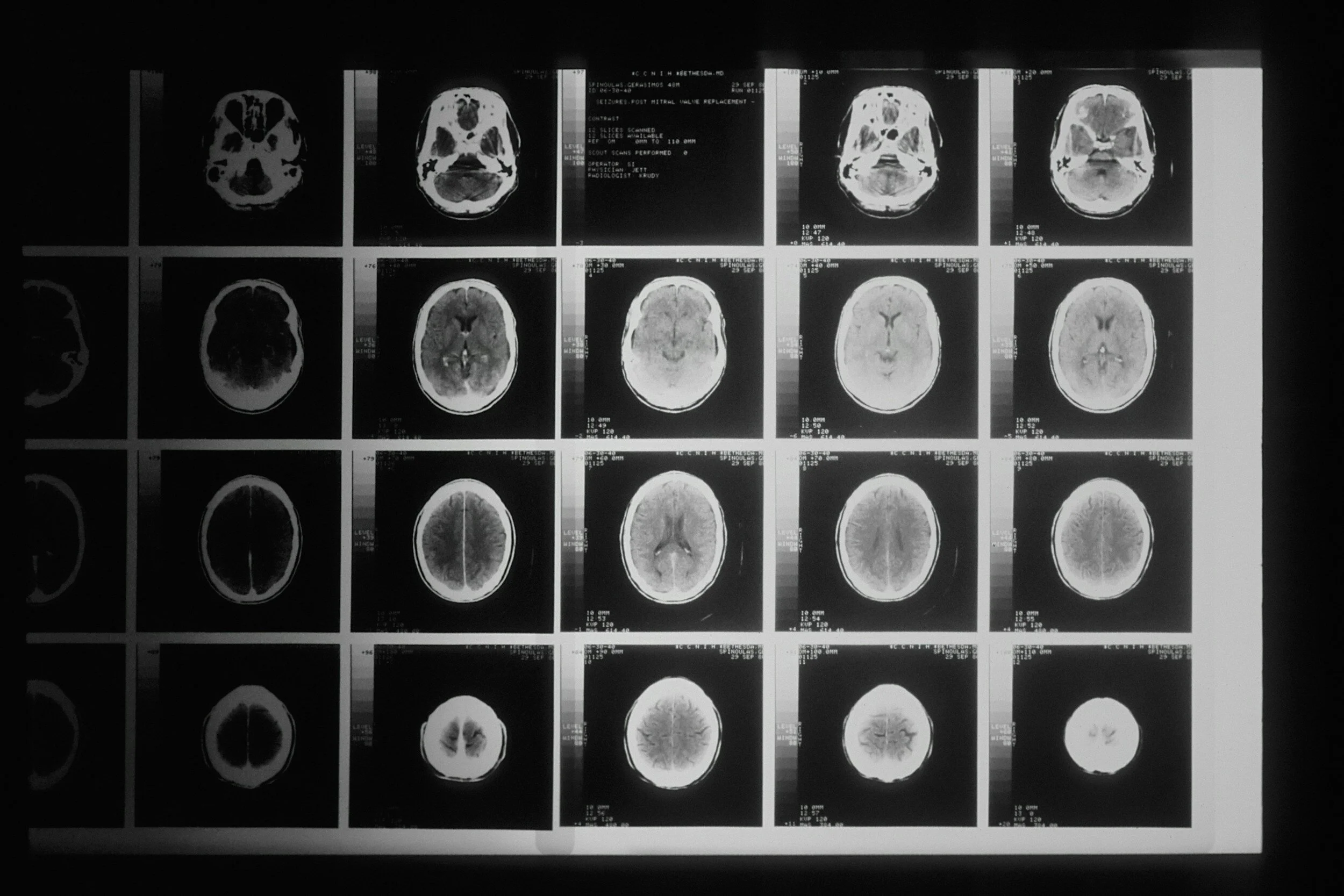

To fully grasp the complexity of neurodiversity, one has to start with the brain. When Debbie Reber used the term ‘differently wired’, she was not exaggerating. Squiggly brains – as ADHD brains have been fashionably renamed on TikTok and Instagram – are a little different to neurotypical ones. According to an extensive review of ADHD patients’ brain scans conducted by Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre in 2018, ADHD brain development is slower (even by 1-3 years), especially in the front parts that help control attention and impulsivity. Additionally, parts of the brain responsible for emotional processing and impulse control – the amygdala and hippocampus, are smaller in the brains of people with ADHD.

After my family’s slightly chaotic journey to the ADHD diagnosis (taking us more than a year and a trip through both private and public health systems), we managed to find my son a supportive psychologist and get the school on board. After that, the path ahead did not suddenly become easier or clearer. Since ADHD often comes in a package with other mental health ailments, such as low self-worth, anxiety or depression, new questions come up almost as soon as we’ve solved old dilemmas. Should we or should we not medicate? If we do, how do we assess whether the benefits – increased control and focus – outweigh the cons – social anxiety and trouble falling asleep?

According to the Under the Radar Report, released by ADHD Australia during the pandemic, anxiety in those with ADHD has skyrocketed since 2020, with 52.4 per cent of children and 64.7 per cent of adults reporting an increase. At the same time, access to mental health support has stalled, with waitlists to see a psychologist exceeding six months. And that’s a real tragedy – because the mainstay of the management of ADHD is having behavioural and psychological strategies available and accessible to everyone.

Interconnected vessel

As a parent, how do you balance managing your neurodivergent child’s physical, social and behavioural needs without neglecting your duties as an employee or entrepreneur, husband or wife, a parent of another child, and a child of your ageing parents who also might need support? And where do your own needs land in that busy, overwhelmed scenario?

Family is an interconnected vessel. We exist in relation to one another – a child or children responding to their parent’s behaviour, and vice-versa. So, when one family member is visibly struggling, foundations can get shaky.

Stressed and guilty, we can’t lead our children onto the path of wellbeing. It’s obvious, but we forget that nobody can pour from an empty cup, not even the most superhuman Mama Bear. The tightroping act of being everything to everyone will quickly start feeling unbearable, most likely resulting in depression, anxiety and burnout.

And that’s why it’s so vital for neurodivergent families to invest in a solid mental health scaffolding of their own. Its first layer is self-enquiry, and the second – is community.

Care for your inner child

Hard times that our neurodiverse kids will undoubtedly experience, possibly more intensely than their neurotypical peers, really teach us all the things we need to know about ourselves. It is as if the buttons they press are the dustiest cabinets that need to be cleaned and aired out. Because we are a sum of different parts – of the ways we were parented and loved, the events we experienced and all the people we have met along the way. “The cry we hear from deep in our hearts always comes from the wounded child within,” Thich Nhat Hanh writes beautifully in his book Reconciliation: Healing The Inner Child.

“In life, achievement is not the most important thing. Authenticity is. The authentic person experiences self-reality by knowing, being and becoming a credible, responsive person,” wrote American psychologist Muriel James in her 1971 bestseller Born to Win. In this book (and others too – she wrote 19 and lived to be 100 years old!), James popularised the concept of ‘self-reparenting’ for survivors of a difficult childhood. One of the tools she recommended was envisioning what an ideal parent would be like and rewriting the script of one’s childhood story with this new parent in place. This can be done alone, during meditation or journaling, or with the help of a therapist.

In our kids, we get to see an old version of ourselves, which can be triggering. So if your sensory-avoidant kid’s blunt refusal to brush their teeth opens an old wound of not being heard, try to calm your inner child first. If your children are fussy about food and you find yourself returning to a memory of an eating disorder, take care of your pain with compassion and love.

When my son once exclaimed that he hates being different, a void opened in my heart, and I know I couldn’t have related to his experiences more.

Because, in a weirdly interconnected world of intergenerational trauma, I, too, had often felt different as a child – and thus alone and misunderstood.

Overall, being around neurodiverse kids is often messy, physical, loud and stressful. The parents’ nervous systems need to be in top condition to help their children go through all the trials and tribulations of learning how to self-regulate and exist in a highly stimulating, competitive world.

Doing it together

Parenting is hard as it is, whether your kids are neurodivergent or not. And the modern way of ‘doing it all alone’ goes against the grain of what we have become so proud of – human evolution. In her famous book, Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding, Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, one of America’s most renowned anthropologists and primatologists, argues that humans – in contrast with other apes – evolved as cooperative breeders, with mothers who had to strongly rely upon others, especially grandmothers, to help with food acquisition and childcare. “No other species proves as clever (…) and inventive as humans in the manufacture of partners to share parenting with. Grandmothers were humankind’s ace in the hole,” she explains.

With time, other helpers – fathers, aunts, uncles and siblings – also became very important in raising kids. Mothers and their young children were truly enmeshed in larger kinship groups and communities that helped with childcare and other tasks, and that cooperation allowed families to have more kids, peace of mind and fresh food on their plates.

We need a neurodivergent community and neurotypical allies to survive.

And even though there’s no simple formula to make a neurodiverse family work smoothly all the time, some things are proven to work well. As a parent, caring for your nervous system is paramount – it’s like putting your oxygen first on the plane. Having people with a shared experience of neurodiversity helps, too, as does access to professional mental health support for both your child and yourself. Learning soothing tools like breathing and meditation can help everyone co-regulate and ground, and spending plenty of time outdoors, as trivial as it sounds, increases the quality of life like nothing else. Overall, through ebbs and flows, ups and downs, every family can establish their own identity and strong family roots. And as every gardener will tell you – healthy roots and key to robust growth. Because a well-rooted tree will rarely fall.